Home » Archives for 2012

Sunday, December 30, 2012

METHOD—TECHNICAL ANALYSIS

Will this stock rise or fall? Should you go long or short? Traders reachfor a multitude of tools to find answers to these questions. Many tie themselves into knots trying to choose between pattern recognition, computerized indicators, artificial intelligence, or even astrology for some desperate souls. No one can learn all the analytic methods, just as no one can master every field of medicine. A physician cannot become a specialist in heart surgery, obstetrics, and psychiatry. No trader can know everything about the markets. You have to find a niche that attracts you and specialize in it.

Markets emit huge volumes of information. Our tools help organize these flows into a manageable form. It is important to select analytic tools and techniques that make sense to you, put them together into a coherent system, and focus on money management. When we make our trading decisions at the right edge of the chart, we deal with probabilities, not certainties. If you want certainty, go to the middle of the chart and try to find a broker who will accept your orders.

This chapter on technical analysis shows how one trader goes about analyzing markets. Use it as a model for choosing your favorite tools, rather than following it slavishly. Test any method you like on your own data because only personal testing will convert information into knowledge and make these methods your own. Many concepts in this book are illustrated with charts. I selected them from a broad range of markets—stocks as well as futures. Technical analysis is a universal language, even though the accents differ. You can apply what you’ve learned from the chart of IBM to silver or Japanese yen. I trade mostly in the United States, but have used the same methods in Germany.

Russia, Singapore, and Australia. Knowing the language of technical analysis enables you to read any market in the world. Analysis is hard, but trading is much harder. Charts reflect what has happened. Indicators reveal the balance of power between bulls and bears. Analysis is not an end in itself, unless you get a job as an analyst for a company. Our job as traders is to make decisions to buy, sell, or stand aside on the basis of our analysis. After reviewing each chart, you need to go to its hard right edge and decide whether to bet on bulls, bet on bears, or stand aside. You must follow up chart analysis by establishing profit targets, setting stops, and applying money management rules.

BASIC CHARTING

A trade is a bet on a price change. You can make money buying low and selling high or shorting high and covering low. Prices are central to our enterprise, yet few traders stop to think what prices are. What exactly are we trying to analyze?

Financial markets consist of huge crowds of people who meet on the floor of an exchange, on the phone, or via the Internet. We can divide them into three groups: buyers, sellers, and undecided traders. Buyers want to buy as cheaply as possible. Sellers want to sell as expensively as possible. They could take forever to negotiate, but feel pressure from undecided traders. They have to act quickly, before some undecided trader makes up his mind, jumps into the game, and takes away their bargain. Undecided traders are the force that speeds up trading. They are true market participants, as long as they watch the market and have the money to trade it. Each deal is struck in the midst of the market crowd, putting pressure on both buyers and sellers. This is why each trade represents the current emotional state of the entire market crowd. Price is a consensus of value of all market participants expressed in action at the moment of the trade.

Many traders have no clear idea what they are trying to analyze. Balance sheets of companies? Pronouncements of the Federal Reserve? Weather reports from soybean-growing states? The cosmic vibrations of Gann theory? Every chart serves as an ongoing poll of the market. Each tick represents a momentary consensus of value of all market participants. High and low prices, the height of every bar, the angle of every trendline, the duration of every pattern reflect aspects of crowd behavior. Recognizing these patterns can help us decide when to bet on bulls or bears. During an election campaign pollsters call thousands of people asking how they’ll vote. Well-designed polls have predictive value, which is why politicians pay for them. Financial markets run on a two-party system—bulls and bears, with a huge silent majority of undecided traders who may throw their weight to either party. Technical analysis is a poll of market participants.

If bulls are on top, we should cover shorts and go long. If bears are stronger, we should go short. If an election is too close to call, a wise trader stands aside. Standing aside is a legitimate market position and the only one in which you can’t lose money. Individual behavior is difficult to predict. Crowds are much more primitive and their behavior more repetitive and predictable. Our job is not to argue with the crowd, telling it what’s rational or irrational. We need to identify crowd behavior and decide how likely it is to continue. If the trend is up and we find that the crowd is growing more optimistic, we should trade that market from the long side. When we find that the crowd is becoming less optimistic, it is time to sell. If the crowd seems confused, we should stand aside and wait for the market to make up its mind.

The Meaning of Prices

Highs and lows, opening and closing prices, intraday swings and weekly ranges reflect crowd behavior. Our charts, indicators, and technical tools are windows into the mass psychology of the markets. You have to be clear about what you are studying if you want to get closer to the truth. Many market participants have backgrounds in science and engineering and are often tempted to apply the principles of physics. For example, they may try to filter out the noise of a trading range to obtain a clear signal of a trend. Those methods can help, but they cannot be converted into automatic trading systems because the markets are not physical processes. They are reflections of crowd psychology, which follows different, less precise laws. In physics, if you calculate everything, you’ll predict where a process will take you. Not so in the markets, where a crowd can always throw you a curve. Here you have to act within this atmosphere of uncertainty, which is why you must protect yourself with good money management.

The Open The opening price, the first price of the day, is marked on a bar chart by a tick pointing to the left. An opening price reflects the influx of overnight orders. Who placed those orders? A dentist who read a tip in a magazine after dinner, a teacher whose broker touted a trade but who needed his wife’s permission to buy, a financial officer of a slow-moving institution who sat in a meeting all day waiting for his idea to be approved by a committee. They are the people who place orders before the open. Opening prices reflect opinions of less informed market participants.

When outsiders buy or sell, who takes the opposite side of their trades? Market professionals step in to help, only they do not run a charity. If floor traders see more buy orders coming in, they open the market higher, forcing outsiders to overpay. The pros go short, so that the slightest dip makes them money. If the crowd is fearful before the opening and sell orders predominate, the floor opens the market very low. They acquire their goods on the cheap, so that the slightest bounce earns them short-term profits. The opening price establishes the first balance of the day between outsiders and insiders, amateurs and professionals. If you are a short-term trader, pay attention to the opening range—the high and the low of the first 15 to 30 minutes of trading. Most opening ranges are followed by breakouts, which are important because they show who is taking control of the market. Several intraday trading systems are based on following opening range breakouts.

The High Why do prices go up? The standard answer—more buyers than sellers—makes no sense because for every trade there is a buyer and a seller. The market goes up when buyers have more money and are more enthusiastic than sellers. Buyers make money when prices go up. Each uptick adds to their profits. They feel flushed with success, keep buying, call friends and tell them to buy—this thing is going up!Eventually, prices rise to a level where bulls have no more money to spare and some start taking profits. Bears see the market as overpriced and hit it with sales. The market stalls, turns, and begins to fall, leaving behind the high point of the day. That point marks the greatest power of bulls for that day.

The high of every bar reflects the maximum power of bulls during that bar. It shows how high bulls could lift the market during that time period. The high of a daily bar reflects the maximum power of bulls during that day, the high of a weekly bar shows the maximum power of bulls during that week, and the high of a five-minute bar shows their maximum power in those five minutes.

The Low Bears make money when prices fall, with each downtick making money for short sellers. As prices slide, bulls become more and more skittish. They cut back their buying and step aside, figuring they’ll be able to pick up what they want cheaper at a later time. When buyers pull in their horns, it becomes easier for bears to push prices lower, and the decline continues.

It takes money to sell stocks short, and a fall in prices slows down when bears start running low on money. Bullish bargain hunters appear on the scene. Experienced traders recognize what’s happening and start covering shorts and going long. Prices rally from their lows, leaving behind the low mark—the lowest tick of the day. The low point of each bar reflects the maximum power of bears during that bar. The lowest point of a daily bar reflects the maximum power of bears during that day, the low point of a weekly bar shows the maximum power of bears during that week, and the low of a five-minute bar shows the maximum power of bears during those five minutes. Several years ago I designed an indicator, called Elder-ray, for tracking the relative power of bulls and bears by measuring how far the high and the low of each bar get away from the average price.

The Close The closing price is marked on a bar chart by a tick pointing to the right. It reflects the final consensus of value for the day. This is the price at which most people look in their daily newspapers. It is especially important in the futures markets, because the settlement of trading accounts depends on it. Professional traders monitor markets throughout the day. Early in the day they take advantage of opening prices, selling high openings and buying low openings, and then unwinding those positions. Their normal mode of operations is to fade—trade against—market extremes and for the return to normalcy. When prices reach a new high and stall, professionals sell, nudging the market down. When prices stabilize after a fall, they buy, helping the market rally. The waves of buying and selling by amateurs that hit the market at the opening usually subside as the day goes on. Outsiders have done what they planned to do, and near the closing time the market is dominated by professional traders.

Closing prices reflect the opinions of professionals. Look at any chart, and you’ll see how often the opening and closing ticks are at the opposite ends of a price bar. This is because amateurs and professionals tend to be on the opposite sides of trades. Candlesticks and Point and Figure Bar charts are most widely used for tracking prices, but there are other methods. Candlestick charts became popular in the West in the 1990s. Each candle represents a day of trading with a body and two wicks, one above and another below. The body reflects the spread between the opening and closing prices. The tip of the upper wick reaches the highest price of the day and the lower wick the lowest price of the day. Candlestick chartists believe that the relationship between the opening and closing prices is the most important piece of daily data. If prices close higher than they opened, the body of the candle is white, but if prices close lower, the body is black.

The height of a candle body and the length of its wicks reflect the battles between bulls and bears. Those patterns, as well as patterns for med by several neighboring candles, provide useful insights into the power struggle in the markets and can help us decide whether to go long or short. The trouble with candles is they are too fat. I can glance at a computer screen with a bar chart and see five to six months of daily data, without squeezing the scale. Put a candlestick chart in the same space, and you’ll be lucky to get two months of data on the screen. Ultimately, a candlestick chart doesn’t reveal anything more than a bar chart. If you draw a normal bar chart and pay attention to the relationships of opening and closing prices, augmenting that with several technical indicators, you’ll be able to read the markets just as well and perhaps better. Candlestick charts are useful for some but not all traders. If you like them, use them. If not, focus on your bar charts and don’t worry about missing something essential.

Point and figure (P&F) charts are based solely on prices, ignoring volume. They differ from bar and candlestick charts by having no horizontal time scale. When markets become inactive, P&F charts stop drawing because they add a new column of X’s and O’s only when prices change beyond a certain trigger point. P&F charts make congestion areas stand out, helping traders find support and resistance and providing targets for reversals and profit taking. P&F charts are much older than bar charts. Professionals in the pits sometimes scribble them on the backs of their trading decks.

Choosing a chart is a matter of personal choice. Pick the one that feels most comfortable. I prefer bar charts but know many serious traders who like P&F charts or candlestick charts.

The Reality of the Chart

Price ticks coalesce into bars, and bars into patterns, as the crowd writes its emotional diary on the screen. Successful traders learn to recognize a few patterns and trade them. They wait for a familiar pattern to emerge like fishermen wait for a nibble at a riverbank where they fished many times in the past. Many amateurs jump from one stock to another, but professionals tend to trade the same markets for years. They learn their intended catch’s personality, its habits and quirks. When professionals see a short-term bottom in a familiar stock, they recognize a bargain and buy. Their buying checks the decline and pushes the stock up. When prices rise, the pros reduce their buying, but amateurs rush in, sucked in by the good news. When markets become overvalued, professionals start unloading their inventory.

Their selling checks the rise and pushes the market down. Amateurs become spooked and start dumping their holdings, accelerating the decline. Once weak holders have been shaken out, prices slide to the level where professionals see a bottom, and the cycle repeats. That cycle is not mathematically perfect, which is why mechanical systems tend not to work. Using technical indicators requires judgment. Before we review specific chart patterns, let us agree on the basic definitions: An uptrend is a pattern in which most rallies reach a higher point than the preceding rally; most declines stop at a higher level than the preceding decline.

A downtrend is a pattern in which most declines fall to a lower point than the preceding decline; most rallies rise to a lower level than the preceding rally. An uptrendline is a line connecting two or more adjacent bottoms, slanting upwards; if we draw a line parallel to it across the tops, we’ll have a trading channel.

A downtrendline is a line connecting two or more adjacent tops, slanting down; one can draw a parallel line across the bottoms, marking a trading channel.

Support is marked by a horizontal line connecting two or more adjacent bottoms. One can often draw a parallel line across the tops, marking a trading range. sistance is marked by a horizontal line connecting two or more adjacent tops. One can often draw a parallel line below, across the bottoms, to mark a trading range. Tops and Bottoms The tops of rallies mark the areas of the maximum power of bulls. They would love to lift prices even higher and make more money, but that’s where they get overpowered by bears. The bottoms of declines, on the other hands, are the areas of maximum power of bears. They would love to push prices even lower and profit from short positions, but they get overpowered by bulls. Use a computer or a ruler to draw a line connecting nearby tops. If it slants up, it shows that bulls are becoming stronger which is a good thing to know if you plan to trade from the long side. If that line slants down, it shows that bulls are becoming weaker and buying is not such a good idea.

Trendlines applied to market bottoms help visualize changes in the power of bears. When a line connecting two nearby bottoms slants down, it shows that bears are growing stronger, and short selling is a good option. If that line slants up, however it shows that bear are becoming weaker. Uptrendlines and Downtrendlines Prices often appear to travel along invisible roads. When peaks rise higher at each successive rally, prices are in an uptrend. When bottoms keep falling lower and lower, prices are in a downtrend.

We can identify uptrends by drawing trendlines connecting the bottoms of declines. We use bottoms to identify an uptrend because the peaks of rallies tend to be expansive, uneven affairs during uptrends. The declines tend to be more orderly, and when you connect them with a trendline, you get a truer picture of that uptrend. We identify downtrends by drawing trendlines across the peaks of rallies. Each new low in a downtrend tends to be lower than the preceding low, but the panic among weak holders can make bottoms irregularly sharp. Drawing a downtrendline across the tops of rallies paints a more correct picture of that downtrend. The most important feature of a trendline is the direction of its slope.

When it rises, the bulls are in control, and when it declines, the bears are in charge. The longer the trendline and the more points of contact it has with prices, the more valid it is. The angle of a trendline reflects the emotional temperature of the crowd. Quiet, shallow trends can last a long time. As trends accelerate, trendlines have to be redrawn, making them steeper. When they rise or fall at 60° or more, their breaks tend to lead to major reversals. This sometimes happens near the tail ends of runaway moves.

You can plot these lines using a ruler or a computer. It is better to draw trendlines as well as support and resistance lines across the edges of congestion areas instead of price extremes. Congestion areas reflect crowd behavior, while the extreme points show only the panic among the weakest crowd members. Tails—The Kangaroo Pattern Trends take a long time to form, but tails are created in just a few days. They provide valuable insights into market psychology, mark reversal areas, and point to trading opportunities. A tail is a one-day spike in the direction of a trend, followed by a reversal. It takes a minimum of three bars to create a tail—relatively narrow bars in the beginning and at the end, with an extremely wide bar in the middle. That middle bar is the tail, but you won’t know for sure until the following day, when a bar has sharply narrowed back at the base, letting the tail hang out. A tail sticks out from a tight weave of prices—you can’t miss it.

A kangaroo, unlike a horse or a dog, propels itself by pushing with its tail. You can always tell which way a kangaroo is going to jump—opposite its tail. When the tail points north, the kangaroo jumps south, and when the tail points south, it jumps north. Market tails tend to occur at turning points in the markets, which recoil from them like kangaroos recoil from their tails. A tail does not forecast the extent of a move, but the first jump usually lasts a few days, offering a trading opportunity. You can do well by recognizing tails and trading against them. Before you trade any pattern, you must understand what it tells you about the market. Why do markets jump away from their tails? Exchanges are owned by members who profit from volume rather than trends. Markets fluctuate, looking for price levels that will bring the highest volume of orders. Members do not know where those levels are, but they keep probing higher and lower. A tail shows that the market has tested a certain price level and rejected it.

If a market stabs down and recoils, it shows that lower prices do not attract volume. The natural thing for the market to do next is rally and test higher levels to see whether higher prices will bring more volume. If the market stabs higher and recoils, leaving a tail pointing upward, it shows that higher prices do not attract volume. The members are likely to sell the market down in order to find whether lower prices will attract volume. Tails work because the owners of the market are looking to maximize income. Whenever you see a very tall bar (several times the average for recent months) shooting in the direction of the existing trend, be alert to the possibility of a tail. If the following day the market traces a very narrow bar at the base of the tall bar, it completes a tail. Be ready to put on a position, trading against that tail, before the close.

When a market hangs down a tail, go long in the vicinity of the base of that tail. Once long, place a protective stop approximately half-way down the tail. If the market starts chewing its tail, run without delay. The targets for profit taking on these long positions are best established by using moving averages and channels (see “Indicators—Five Bullets to a Clip,” page 84). When a market puts up a tail, go short in the area of the base of that tail. Once short, place a protective stop approximately half-way up the tail. If the market starts rallying up its tail, it is time to run; do not wait for the entire tail to be chewed up. Establish profit-taking targets using moving averages and channels. You can trade against tails in any timeframe. Daily charts are most common, but you can also trade them on intraday or weekly charts. The magnitude of a move depends on its timeframe. A tail on a weekly chart will generate a much bigger move than a tail on a five-minute chart.

Support, Resistance, and False Breakouts When most traders and investors buy and sell, they make an emotional as well as a financial commitment to their trade. Their emotions can propel market trends or send them into reversals.

The longer a market trades at a certain level, the more people buy and sell. Suppose a stock falls from 80 and trades near 70 for several weeks, until many believe that it has found support and reached its bottom. What happens if heavy selling comes in and shoves that stock down to 60? Smart longs will run fast, banging out at 69 or 68. Others will sit through the entire painful decline. If losers haven’t given up near 60 and are still alive when the market trades back towards 70, their pain will prompt them to jump at a chance to “get out even.” Their selling is likely to cap a rally, at least temporarily. Their painful memories are the reason why the areas that served as support on the way down become resistance on the way up, and vice versa.

Regret is another psychological force behind support and resistance. If a stock trades at 80 for a while and then rallies to 95, those who did not buy it near 80 feel as if they missed the train. If that stock sinks back near 80, traders who regret a missed opportunity will return to buy in force. Support and resistance can remain active for months or even years because investors have long memories. When prices return to their old levels, some jump at the opportunity to add to their positions while others see a chance to get out. Whenever you work with a chart, draw support and resistance lines across recent tops and bottoms. Expect a trend to slow down in those areas, and use them to enter positions or take profits. Keep in mind that support and resistance are flexible—they are like a ranch wire fence rather than a glass wall. A glass wall is rigid and shatters when broken, but a herd of bulls can push against a wire fence, shove their muzzles through it, and it will lean but stand. Markets have many false breakouts below support and above resistance, with prices returning into their range after a brief violation.

A false upside breakout occurs when the market rises above resistance and sucks in buyers before reversing and falling. A false downside breakout occurs when prices fall below support, attracting more bears just before a rally. False breakouts provide professionals with some of the best trading opportunities. They are similar to tails, only tails have a single wide bar, whereas false breakouts can have several bars, none of them especially tall. What causes false breakouts and how do you trade them? At the end of a long rise the market hits resistance, stops, and starts churning. The professionals know there are many more buy orders above the resistance level. Some were placed by traders looking to buy a new breakout, and others are protective stops placed by those who went short on the way up. The pros are the first to know where people have stops because they are the ones holding the orders.

A false breakout occurs when the pros organize a fishing expedition to run stops. For example, when a stock is slightly below its resistance at 60, the floor may start loading up on longs near 58.85. As sellers pull back, the market roars above 60, setting off buy stops. The floor starts selling into that rush, unloading longs as prices touch 60.50. When they see that public buy orders are drying up, they sell short and prices tank back below 60. That’s when your charts show a false breakout above 60. S&P 500 futures are notorious for false breakouts. Day after day this market exceeds its previous day’s high or falls below its previous day’s low by a few ticks (a tick is the minimum price change permitted by the exchange where an instrument is traded). This is one of the reasons the S&P is a difficult market to trade, but it attracts beginners like flies. The floor has a field day slapping them.

Some of the best trading opportunities occur after false breakouts. When prices fall back into the range after a false upside breakout, you have extra confidence to trade short. Use the top of the false breakout as your stoploss point. Once prices rally back into their range after a false downside breakout, you have extra confidence to trade long. Use the bottom of that false breakout for your stop-loss point. If you have an open position, defend yourself against false breakouts by reducing your trading size and placing wider stops. Be ready to reposition if stopped out of your trade. There are many advantages to risking just a small fraction of your account on any trade. It allows you to be more flexible with stops. When the volatility is high, consider protecting a long position by buying a put or a short position by buying a call. Finally, if you get stopped out on a false breakout, don’t be shy about getting back into a trade. Beginners tend to make a single stab at a position and stay out if they are stopped out. Professionals, on the other hand, will attempt several entries before nailing down the trade they want. Double Tops and Bottoms Bulls make money when the market rises. There are always a few who take profits on the way up, but new bulls come in and the rally continues. Every rally reaches a point where enough bulls look at it and say—this is very nice, and it may get even nicer, but I’d rather have cash. Rallies top out after enough wealthy bulls take their profits, while the money from new bulls is not enough to replace what was taken out.

When the market heads down from its peak, savvy bulls, the ones who’ve cashed out early, are the most relaxed group. Other bulls who are still long, especially if they came in late, feel trapped. Their profits are melting away and turning into losses. Should they hold or sell? If enough moneyed bulls decide the decline is being overdone, they’ll step in and buy. As the rally resumes, more bulls come in. Now prices approach the level of their old top, and that’s where you can expect sell orders to hit the market. Many traders who got caught in the previous decline swear to get out if the market gives them a second chance. As the market rises toward its previous peak, the main question is whether it will it rise to a new high or form a double top and turn down. Technical indicators can be of great help in answering this question. When they rise to a new high, they tell you to hold, and when they form bearish divergences, they tell you to take profits at the second top.

A mirror image of this situation occurs at market bottoms. The market falls to a new low at which enough smart bears start covering shorts and the market rallies. Once that rally peters out and prices start sinking again, all eyes are on the previous low—will it hold? If bears are strong and bulls skittish, prices will break below the first low, and the downtrend will continue. If bears are weak and bulls are strong, the decline will stop in the vicinity of the old low, creating a double bottom. Technical indicators help decipher which of the two is more likely to happen. Triangles A triangle is a congestion area, a pause when winners take profits and new trend followers get aboard, while their opponents trade against the preceding trend. It is like a train station. The train stops to let passengers off and pick up new ones, but there is always a chance this is the last stop on the line and it may turn back. The upper boundary of a triangle shows where sellers overpower buyers and prevent the market from rising. The lower boundary shows where buyers overpower sellers and prevent the market from falling. As the two start to converge, you know a breakout is coming. As a general rule, the trend that preceded the triangle deserves the benefit of the doubt. The angles between triangle walls reflect the balance of power between bulls and bears and hint at the likely direction of a breakout.

An ascending triangle has a flat upper boundary and a rising lower boundary. The flat upper line shows that bears have drawn a line in the sand and sell whenever the market comes to it. They must be a pretty powerful group, calmly waiting for prices to come to them before unloading. At the same time buyers are becoming more aggressive. They snap up merchandise and keep raising the floor under the market. On what party should you bet? Nobody knows who’ll win the election, but savvy traders tend to place buy orders slightly above the upper line of an ascending triangle. Since sellers are on the defensive, if the attacking bulls succeed, the breakout is likely to be steep. This is the logic of buying upside breakouts from ascending triangles.

A descending triangle has a flat lower boundary and a declining upper boundary. The horizontal lower line shows that bulls are pretty determined, calmly waiting to buy at a certain level. At the same time, sellers are becoming more aggressive. They keep selling at lower and lower levels, pushing the market closer to the line drawn by buyers. As a trader, which way will you bet—on the bulls or the bears? Experienced traders tend to place their orders to sell short slightly below the lower line of a descending triangle. Let buyers defend that line, but if bulls collapse after a long defense, a break is likely to be sharp. This is the logic of shorting downside breakouts from descending triangles. A symmetrical triangle shows that both bulls and bears are equally confident. Bulls keep paying up, and bears keep selling lower. Neither group is backing off, and their fight must be resolved before prices reach the tip of the triangle. The breakout is likely to go in the direction of the trend that preceded the triangle. Volume Each unit of volume represents the actions of two individuals—a buyer and a seller. It can be measured by several numbers: shares, contracts, or dollars that have changed hands. Volume is usually plotted as a histogram below prices. It provides important clues about the actions of bulls and bears. Rising volume tends to confirm trends, and falling volume brings them into question.

Volume reflects the level of pain among market participants. At each tick in every trade, one person is winning and the other losing. Markets can move only if enough new losers enter the game to supply profits to winners. If the market is falling, it takes a very courageous or reckless bull to step in and buy, but without him there is no increase in volume. When the trend is up, it takes a very brave or reckless bear to step in and sell. Rising volume shows that losers are continuing to come in, allowing the trend to continue. When losers start abandoning the market, volume falls, and the trend runs out of steam. Volume gives traders several useful clues. A one-day splash of uncommonly high volume often marks the beginning of a trend when it accompanies a breakout from a trading range. A similar splash tends to mark the end of a trend if it occurs during a wellestablished move. Exceedingly high volume, three or more times above average, identifies market hysteria. That is when nervous bulls finally decide that the uptrend is for real and rush in to buy or nervous bears become convinced that the decline has no bottom and jump in to sell short.

Markets emit huge volumes of information. Our tools help organize these flows into a manageable form. It is important to select analytic tools and techniques that make sense to you, put them together into a coherent system, and focus on money management. When we make our trading decisions at the right edge of the chart, we deal with probabilities, not certainties. If you want certainty, go to the middle of the chart and try to find a broker who will accept your orders.

This chapter on technical analysis shows how one trader goes about analyzing markets. Use it as a model for choosing your favorite tools, rather than following it slavishly. Test any method you like on your own data because only personal testing will convert information into knowledge and make these methods your own. Many concepts in this book are illustrated with charts. I selected them from a broad range of markets—stocks as well as futures. Technical analysis is a universal language, even though the accents differ. You can apply what you’ve learned from the chart of IBM to silver or Japanese yen. I trade mostly in the United States, but have used the same methods in Germany.

Russia, Singapore, and Australia. Knowing the language of technical analysis enables you to read any market in the world. Analysis is hard, but trading is much harder. Charts reflect what has happened. Indicators reveal the balance of power between bulls and bears. Analysis is not an end in itself, unless you get a job as an analyst for a company. Our job as traders is to make decisions to buy, sell, or stand aside on the basis of our analysis. After reviewing each chart, you need to go to its hard right edge and decide whether to bet on bulls, bet on bears, or stand aside. You must follow up chart analysis by establishing profit targets, setting stops, and applying money management rules.

BASIC CHARTING

A trade is a bet on a price change. You can make money buying low and selling high or shorting high and covering low. Prices are central to our enterprise, yet few traders stop to think what prices are. What exactly are we trying to analyze?

|

| Technical Analysis |

Many traders have no clear idea what they are trying to analyze. Balance sheets of companies? Pronouncements of the Federal Reserve? Weather reports from soybean-growing states? The cosmic vibrations of Gann theory? Every chart serves as an ongoing poll of the market. Each tick represents a momentary consensus of value of all market participants. High and low prices, the height of every bar, the angle of every trendline, the duration of every pattern reflect aspects of crowd behavior. Recognizing these patterns can help us decide when to bet on bulls or bears. During an election campaign pollsters call thousands of people asking how they’ll vote. Well-designed polls have predictive value, which is why politicians pay for them. Financial markets run on a two-party system—bulls and bears, with a huge silent majority of undecided traders who may throw their weight to either party. Technical analysis is a poll of market participants.

If bulls are on top, we should cover shorts and go long. If bears are stronger, we should go short. If an election is too close to call, a wise trader stands aside. Standing aside is a legitimate market position and the only one in which you can’t lose money. Individual behavior is difficult to predict. Crowds are much more primitive and their behavior more repetitive and predictable. Our job is not to argue with the crowd, telling it what’s rational or irrational. We need to identify crowd behavior and decide how likely it is to continue. If the trend is up and we find that the crowd is growing more optimistic, we should trade that market from the long side. When we find that the crowd is becoming less optimistic, it is time to sell. If the crowd seems confused, we should stand aside and wait for the market to make up its mind.

The Meaning of Prices

Highs and lows, opening and closing prices, intraday swings and weekly ranges reflect crowd behavior. Our charts, indicators, and technical tools are windows into the mass psychology of the markets. You have to be clear about what you are studying if you want to get closer to the truth. Many market participants have backgrounds in science and engineering and are often tempted to apply the principles of physics. For example, they may try to filter out the noise of a trading range to obtain a clear signal of a trend. Those methods can help, but they cannot be converted into automatic trading systems because the markets are not physical processes. They are reflections of crowd psychology, which follows different, less precise laws. In physics, if you calculate everything, you’ll predict where a process will take you. Not so in the markets, where a crowd can always throw you a curve. Here you have to act within this atmosphere of uncertainty, which is why you must protect yourself with good money management.

The Open The opening price, the first price of the day, is marked on a bar chart by a tick pointing to the left. An opening price reflects the influx of overnight orders. Who placed those orders? A dentist who read a tip in a magazine after dinner, a teacher whose broker touted a trade but who needed his wife’s permission to buy, a financial officer of a slow-moving institution who sat in a meeting all day waiting for his idea to be approved by a committee. They are the people who place orders before the open. Opening prices reflect opinions of less informed market participants.

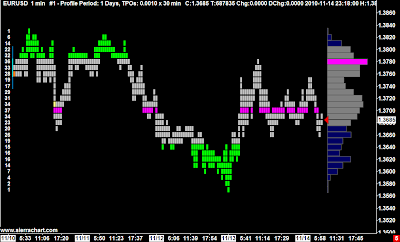

|

| Trade Chart |

The High Why do prices go up? The standard answer—more buyers than sellers—makes no sense because for every trade there is a buyer and a seller. The market goes up when buyers have more money and are more enthusiastic than sellers. Buyers make money when prices go up. Each uptick adds to their profits. They feel flushed with success, keep buying, call friends and tell them to buy—this thing is going up!Eventually, prices rise to a level where bulls have no more money to spare and some start taking profits. Bears see the market as overpriced and hit it with sales. The market stalls, turns, and begins to fall, leaving behind the high point of the day. That point marks the greatest power of bulls for that day.

The high of every bar reflects the maximum power of bulls during that bar. It shows how high bulls could lift the market during that time period. The high of a daily bar reflects the maximum power of bulls during that day, the high of a weekly bar shows the maximum power of bulls during that week, and the high of a five-minute bar shows their maximum power in those five minutes.

The Low Bears make money when prices fall, with each downtick making money for short sellers. As prices slide, bulls become more and more skittish. They cut back their buying and step aside, figuring they’ll be able to pick up what they want cheaper at a later time. When buyers pull in their horns, it becomes easier for bears to push prices lower, and the decline continues.

It takes money to sell stocks short, and a fall in prices slows down when bears start running low on money. Bullish bargain hunters appear on the scene. Experienced traders recognize what’s happening and start covering shorts and going long. Prices rally from their lows, leaving behind the low mark—the lowest tick of the day. The low point of each bar reflects the maximum power of bears during that bar. The lowest point of a daily bar reflects the maximum power of bears during that day, the low point of a weekly bar shows the maximum power of bears during that week, and the low of a five-minute bar shows the maximum power of bears during those five minutes. Several years ago I designed an indicator, called Elder-ray, for tracking the relative power of bulls and bears by measuring how far the high and the low of each bar get away from the average price.

The Close The closing price is marked on a bar chart by a tick pointing to the right. It reflects the final consensus of value for the day. This is the price at which most people look in their daily newspapers. It is especially important in the futures markets, because the settlement of trading accounts depends on it. Professional traders monitor markets throughout the day. Early in the day they take advantage of opening prices, selling high openings and buying low openings, and then unwinding those positions. Their normal mode of operations is to fade—trade against—market extremes and for the return to normalcy. When prices reach a new high and stall, professionals sell, nudging the market down. When prices stabilize after a fall, they buy, helping the market rally. The waves of buying and selling by amateurs that hit the market at the opening usually subside as the day goes on. Outsiders have done what they planned to do, and near the closing time the market is dominated by professional traders.

Closing prices reflect the opinions of professionals. Look at any chart, and you’ll see how often the opening and closing ticks are at the opposite ends of a price bar. This is because amateurs and professionals tend to be on the opposite sides of trades. Candlesticks and Point and Figure Bar charts are most widely used for tracking prices, but there are other methods. Candlestick charts became popular in the West in the 1990s. Each candle represents a day of trading with a body and two wicks, one above and another below. The body reflects the spread between the opening and closing prices. The tip of the upper wick reaches the highest price of the day and the lower wick the lowest price of the day. Candlestick chartists believe that the relationship between the opening and closing prices is the most important piece of daily data. If prices close higher than they opened, the body of the candle is white, but if prices close lower, the body is black.

The height of a candle body and the length of its wicks reflect the battles between bulls and bears. Those patterns, as well as patterns for med by several neighboring candles, provide useful insights into the power struggle in the markets and can help us decide whether to go long or short. The trouble with candles is they are too fat. I can glance at a computer screen with a bar chart and see five to six months of daily data, without squeezing the scale. Put a candlestick chart in the same space, and you’ll be lucky to get two months of data on the screen. Ultimately, a candlestick chart doesn’t reveal anything more than a bar chart. If you draw a normal bar chart and pay attention to the relationships of opening and closing prices, augmenting that with several technical indicators, you’ll be able to read the markets just as well and perhaps better. Candlestick charts are useful for some but not all traders. If you like them, use them. If not, focus on your bar charts and don’t worry about missing something essential.

Point and figure (P&F) charts are based solely on prices, ignoring volume. They differ from bar and candlestick charts by having no horizontal time scale. When markets become inactive, P&F charts stop drawing because they add a new column of X’s and O’s only when prices change beyond a certain trigger point. P&F charts make congestion areas stand out, helping traders find support and resistance and providing targets for reversals and profit taking. P&F charts are much older than bar charts. Professionals in the pits sometimes scribble them on the backs of their trading decks.

Choosing a chart is a matter of personal choice. Pick the one that feels most comfortable. I prefer bar charts but know many serious traders who like P&F charts or candlestick charts.

The Reality of the Chart

Price ticks coalesce into bars, and bars into patterns, as the crowd writes its emotional diary on the screen. Successful traders learn to recognize a few patterns and trade them. They wait for a familiar pattern to emerge like fishermen wait for a nibble at a riverbank where they fished many times in the past. Many amateurs jump from one stock to another, but professionals tend to trade the same markets for years. They learn their intended catch’s personality, its habits and quirks. When professionals see a short-term bottom in a familiar stock, they recognize a bargain and buy. Their buying checks the decline and pushes the stock up. When prices rise, the pros reduce their buying, but amateurs rush in, sucked in by the good news. When markets become overvalued, professionals start unloading their inventory.

Their selling checks the rise and pushes the market down. Amateurs become spooked and start dumping their holdings, accelerating the decline. Once weak holders have been shaken out, prices slide to the level where professionals see a bottom, and the cycle repeats. That cycle is not mathematically perfect, which is why mechanical systems tend not to work. Using technical indicators requires judgment. Before we review specific chart patterns, let us agree on the basic definitions: An uptrend is a pattern in which most rallies reach a higher point than the preceding rally; most declines stop at a higher level than the preceding decline.

A downtrend is a pattern in which most declines fall to a lower point than the preceding decline; most rallies rise to a lower level than the preceding rally. An uptrendline is a line connecting two or more adjacent bottoms, slanting upwards; if we draw a line parallel to it across the tops, we’ll have a trading channel.

A downtrendline is a line connecting two or more adjacent tops, slanting down; one can draw a parallel line across the bottoms, marking a trading channel.

|

| The Reality of The Chart |

Trendlines applied to market bottoms help visualize changes in the power of bears. When a line connecting two nearby bottoms slants down, it shows that bears are growing stronger, and short selling is a good option. If that line slants up, however it shows that bear are becoming weaker. Uptrendlines and Downtrendlines Prices often appear to travel along invisible roads. When peaks rise higher at each successive rally, prices are in an uptrend. When bottoms keep falling lower and lower, prices are in a downtrend.

We can identify uptrends by drawing trendlines connecting the bottoms of declines. We use bottoms to identify an uptrend because the peaks of rallies tend to be expansive, uneven affairs during uptrends. The declines tend to be more orderly, and when you connect them with a trendline, you get a truer picture of that uptrend. We identify downtrends by drawing trendlines across the peaks of rallies. Each new low in a downtrend tends to be lower than the preceding low, but the panic among weak holders can make bottoms irregularly sharp. Drawing a downtrendline across the tops of rallies paints a more correct picture of that downtrend. The most important feature of a trendline is the direction of its slope.

When it rises, the bulls are in control, and when it declines, the bears are in charge. The longer the trendline and the more points of contact it has with prices, the more valid it is. The angle of a trendline reflects the emotional temperature of the crowd. Quiet, shallow trends can last a long time. As trends accelerate, trendlines have to be redrawn, making them steeper. When they rise or fall at 60° or more, their breaks tend to lead to major reversals. This sometimes happens near the tail ends of runaway moves.

You can plot these lines using a ruler or a computer. It is better to draw trendlines as well as support and resistance lines across the edges of congestion areas instead of price extremes. Congestion areas reflect crowd behavior, while the extreme points show only the panic among the weakest crowd members. Tails—The Kangaroo Pattern Trends take a long time to form, but tails are created in just a few days. They provide valuable insights into market psychology, mark reversal areas, and point to trading opportunities. A tail is a one-day spike in the direction of a trend, followed by a reversal. It takes a minimum of three bars to create a tail—relatively narrow bars in the beginning and at the end, with an extremely wide bar in the middle. That middle bar is the tail, but you won’t know for sure until the following day, when a bar has sharply narrowed back at the base, letting the tail hang out. A tail sticks out from a tight weave of prices—you can’t miss it.

A kangaroo, unlike a horse or a dog, propels itself by pushing with its tail. You can always tell which way a kangaroo is going to jump—opposite its tail. When the tail points north, the kangaroo jumps south, and when the tail points south, it jumps north. Market tails tend to occur at turning points in the markets, which recoil from them like kangaroos recoil from their tails. A tail does not forecast the extent of a move, but the first jump usually lasts a few days, offering a trading opportunity. You can do well by recognizing tails and trading against them. Before you trade any pattern, you must understand what it tells you about the market. Why do markets jump away from their tails? Exchanges are owned by members who profit from volume rather than trends. Markets fluctuate, looking for price levels that will bring the highest volume of orders. Members do not know where those levels are, but they keep probing higher and lower. A tail shows that the market has tested a certain price level and rejected it.

If a market stabs down and recoils, it shows that lower prices do not attract volume. The natural thing for the market to do next is rally and test higher levels to see whether higher prices will bring more volume. If the market stabs higher and recoils, leaving a tail pointing upward, it shows that higher prices do not attract volume. The members are likely to sell the market down in order to find whether lower prices will attract volume. Tails work because the owners of the market are looking to maximize income. Whenever you see a very tall bar (several times the average for recent months) shooting in the direction of the existing trend, be alert to the possibility of a tail. If the following day the market traces a very narrow bar at the base of the tall bar, it completes a tail. Be ready to put on a position, trading against that tail, before the close.

When a market hangs down a tail, go long in the vicinity of the base of that tail. Once long, place a protective stop approximately half-way down the tail. If the market starts chewing its tail, run without delay. The targets for profit taking on these long positions are best established by using moving averages and channels (see “Indicators—Five Bullets to a Clip,” page 84). When a market puts up a tail, go short in the area of the base of that tail. Once short, place a protective stop approximately half-way up the tail. If the market starts rallying up its tail, it is time to run; do not wait for the entire tail to be chewed up. Establish profit-taking targets using moving averages and channels. You can trade against tails in any timeframe. Daily charts are most common, but you can also trade them on intraday or weekly charts. The magnitude of a move depends on its timeframe. A tail on a weekly chart will generate a much bigger move than a tail on a five-minute chart.

Support, Resistance, and False Breakouts When most traders and investors buy and sell, they make an emotional as well as a financial commitment to their trade. Their emotions can propel market trends or send them into reversals.

|

| Trend |

Regret is another psychological force behind support and resistance. If a stock trades at 80 for a while and then rallies to 95, those who did not buy it near 80 feel as if they missed the train. If that stock sinks back near 80, traders who regret a missed opportunity will return to buy in force. Support and resistance can remain active for months or even years because investors have long memories. When prices return to their old levels, some jump at the opportunity to add to their positions while others see a chance to get out. Whenever you work with a chart, draw support and resistance lines across recent tops and bottoms. Expect a trend to slow down in those areas, and use them to enter positions or take profits. Keep in mind that support and resistance are flexible—they are like a ranch wire fence rather than a glass wall. A glass wall is rigid and shatters when broken, but a herd of bulls can push against a wire fence, shove their muzzles through it, and it will lean but stand. Markets have many false breakouts below support and above resistance, with prices returning into their range after a brief violation.

A false upside breakout occurs when the market rises above resistance and sucks in buyers before reversing and falling. A false downside breakout occurs when prices fall below support, attracting more bears just before a rally. False breakouts provide professionals with some of the best trading opportunities. They are similar to tails, only tails have a single wide bar, whereas false breakouts can have several bars, none of them especially tall. What causes false breakouts and how do you trade them? At the end of a long rise the market hits resistance, stops, and starts churning. The professionals know there are many more buy orders above the resistance level. Some were placed by traders looking to buy a new breakout, and others are protective stops placed by those who went short on the way up. The pros are the first to know where people have stops because they are the ones holding the orders.

A false breakout occurs when the pros organize a fishing expedition to run stops. For example, when a stock is slightly below its resistance at 60, the floor may start loading up on longs near 58.85. As sellers pull back, the market roars above 60, setting off buy stops. The floor starts selling into that rush, unloading longs as prices touch 60.50. When they see that public buy orders are drying up, they sell short and prices tank back below 60. That’s when your charts show a false breakout above 60. S&P 500 futures are notorious for false breakouts. Day after day this market exceeds its previous day’s high or falls below its previous day’s low by a few ticks (a tick is the minimum price change permitted by the exchange where an instrument is traded). This is one of the reasons the S&P is a difficult market to trade, but it attracts beginners like flies. The floor has a field day slapping them.

Some of the best trading opportunities occur after false breakouts. When prices fall back into the range after a false upside breakout, you have extra confidence to trade short. Use the top of the false breakout as your stoploss point. Once prices rally back into their range after a false downside breakout, you have extra confidence to trade long. Use the bottom of that false breakout for your stop-loss point. If you have an open position, defend yourself against false breakouts by reducing your trading size and placing wider stops. Be ready to reposition if stopped out of your trade. There are many advantages to risking just a small fraction of your account on any trade. It allows you to be more flexible with stops. When the volatility is high, consider protecting a long position by buying a put or a short position by buying a call. Finally, if you get stopped out on a false breakout, don’t be shy about getting back into a trade. Beginners tend to make a single stab at a position and stay out if they are stopped out. Professionals, on the other hand, will attempt several entries before nailing down the trade they want. Double Tops and Bottoms Bulls make money when the market rises. There are always a few who take profits on the way up, but new bulls come in and the rally continues. Every rally reaches a point where enough bulls look at it and say—this is very nice, and it may get even nicer, but I’d rather have cash. Rallies top out after enough wealthy bulls take their profits, while the money from new bulls is not enough to replace what was taken out.

When the market heads down from its peak, savvy bulls, the ones who’ve cashed out early, are the most relaxed group. Other bulls who are still long, especially if they came in late, feel trapped. Their profits are melting away and turning into losses. Should they hold or sell? If enough moneyed bulls decide the decline is being overdone, they’ll step in and buy. As the rally resumes, more bulls come in. Now prices approach the level of their old top, and that’s where you can expect sell orders to hit the market. Many traders who got caught in the previous decline swear to get out if the market gives them a second chance. As the market rises toward its previous peak, the main question is whether it will it rise to a new high or form a double top and turn down. Technical indicators can be of great help in answering this question. When they rise to a new high, they tell you to hold, and when they form bearish divergences, they tell you to take profits at the second top.

A mirror image of this situation occurs at market bottoms. The market falls to a new low at which enough smart bears start covering shorts and the market rallies. Once that rally peters out and prices start sinking again, all eyes are on the previous low—will it hold? If bears are strong and bulls skittish, prices will break below the first low, and the downtrend will continue. If bears are weak and bulls are strong, the decline will stop in the vicinity of the old low, creating a double bottom. Technical indicators help decipher which of the two is more likely to happen. Triangles A triangle is a congestion area, a pause when winners take profits and new trend followers get aboard, while their opponents trade against the preceding trend. It is like a train station. The train stops to let passengers off and pick up new ones, but there is always a chance this is the last stop on the line and it may turn back. The upper boundary of a triangle shows where sellers overpower buyers and prevent the market from rising. The lower boundary shows where buyers overpower sellers and prevent the market from falling. As the two start to converge, you know a breakout is coming. As a general rule, the trend that preceded the triangle deserves the benefit of the doubt. The angles between triangle walls reflect the balance of power between bulls and bears and hint at the likely direction of a breakout.

An ascending triangle has a flat upper boundary and a rising lower boundary. The flat upper line shows that bears have drawn a line in the sand and sell whenever the market comes to it. They must be a pretty powerful group, calmly waiting for prices to come to them before unloading. At the same time buyers are becoming more aggressive. They snap up merchandise and keep raising the floor under the market. On what party should you bet? Nobody knows who’ll win the election, but savvy traders tend to place buy orders slightly above the upper line of an ascending triangle. Since sellers are on the defensive, if the attacking bulls succeed, the breakout is likely to be steep. This is the logic of buying upside breakouts from ascending triangles.

A descending triangle has a flat lower boundary and a declining upper boundary. The horizontal lower line shows that bulls are pretty determined, calmly waiting to buy at a certain level. At the same time, sellers are becoming more aggressive. They keep selling at lower and lower levels, pushing the market closer to the line drawn by buyers. As a trader, which way will you bet—on the bulls or the bears? Experienced traders tend to place their orders to sell short slightly below the lower line of a descending triangle. Let buyers defend that line, but if bulls collapse after a long defense, a break is likely to be sharp. This is the logic of shorting downside breakouts from descending triangles. A symmetrical triangle shows that both bulls and bears are equally confident. Bulls keep paying up, and bears keep selling lower. Neither group is backing off, and their fight must be resolved before prices reach the tip of the triangle. The breakout is likely to go in the direction of the trend that preceded the triangle. Volume Each unit of volume represents the actions of two individuals—a buyer and a seller. It can be measured by several numbers: shares, contracts, or dollars that have changed hands. Volume is usually plotted as a histogram below prices. It provides important clues about the actions of bulls and bears. Rising volume tends to confirm trends, and falling volume brings them into question.

Volume reflects the level of pain among market participants. At each tick in every trade, one person is winning and the other losing. Markets can move only if enough new losers enter the game to supply profits to winners. If the market is falling, it takes a very courageous or reckless bull to step in and buy, but without him there is no increase in volume. When the trend is up, it takes a very brave or reckless bear to step in and sell. Rising volume shows that losers are continuing to come in, allowing the trend to continue. When losers start abandoning the market, volume falls, and the trend runs out of steam. Volume gives traders several useful clues. A one-day splash of uncommonly high volume often marks the beginning of a trend when it accompanies a breakout from a trading range. A similar splash tends to mark the end of a trend if it occurs during a wellestablished move. Exceedingly high volume, three or more times above average, identifies market hysteria. That is when nervous bulls finally decide that the uptrend is for real and rush in to buy or nervous bears become convinced that the decline has no bottom and jump in to sell short.

Labels:

Technical

|

0

comments

THE MATURE TRADER

|

| The Mature Trader |

Successful traders are often unconventional people, and some are very eccentric. When they mix with others, they often break social rules. The markets are set up for the majority to lose money, and a small group of winners marches to a different drummer, in and out of the markets. Markets consist of huge crowds of people watching the same trading vehicles, mesmerized by upticks and downticks. Think of a crowd at a concert or in a movie theater. When the show begins, the crowd gets emotionally in gear and develops an amorphous but powerful mass mind, laughing or weeping together. A mass mind also emerges in the markets, only here it is more malignant. Instead of laughing or weeping, the crowd seeks each trader’s private psychological weakness and hits him in that spot.

Markets seduce greedy traders into buying positions that are too large for their accounts and then destroy them with a reaction they cannot afford to sit out. They shake fearful traders out of winning trades with brief countertrend spikes before embarking on runaway moves. Lazy traders are the favorite victims of the market, which keeps throwing new tricks at the unprepared. Whatever your psychological flaws and fears, whatever your inner demons, whatever your hidden weaknesses and obsessions, the market will seek them out, find them, and use them against you, like a skilled wrestler uses his opponent’s own weight to toss him to the ground. Successful traders have outgrown or overcome their inner demons.

Instead of being tossed by the markets, they maintain their own balance and scan for chinks in the crowd’s armor, so that they can toss the market for a change. They may appear eccentric, but when it comes to trading they are much healthier than the crowd. Being a trader is a journey of self-discovery. Trade long enough, and you will face all your psychological handicaps—anxiety, greed, fear, anger, and sloth. Remember, you’re not in the markets for psychotherapy; self-discovery is a byproduct, not the goal of trading. The primary goal of a successful trader is to accumulate equity. Healthy trading boils down to two questions you need to ask in every trade: “What is my profit target?” and “How will I protect my capital?” A good trader accepts full responsibility for the outcome of every trade. You cannot blame others for taking your money. You have to improve your trading plans and methods of money management. It will take time, and it will take discipline.

Discipline

A friend of mine used to have a dog-training business. Occasionally a prospective client would call her and say, “I want to train my dog to come when called, but I do not want to train it to sit or lie down.” And she’d answer, “Training a dog to come off-leash is one of the hardest things to teach; you must do a lot of obedience training first. What you’re saying sounds like, ‘I want my dog be a neurosurgeon, but I do not want it to go to high school.’” Many new traders expect to sit in front of their screens and make easy money day-trading. They skip high school and head straight for neurosurgery.

|

| Discipline |

As a matter of fact, other market participants want you to be undisciplined and impulsive. That makes it easier for them to get your money. Your defense against self-destructiveness is discipline. You have to set up your own rules and follow them in order to prevent self-sabotage. Discipline means designing, testing, and following your trading system. It means learning to enter and exit in response to predefined signals rather than jumping in and out on a whim. It means doing the right thing, not the easy thing. And the first challenge on the road to disciplined trading involves setting up a record-keeping system.

Record-Keeping

|

| Record-Keeping |

If money is a problem, keeping and reviewing records of all expenditures is certain to uncover wasteful tendencies. Keeping scrupulous records turns a spotlight on a problem and allows you to improve. Becoming a good trader means taking several courses—psychology, technical analysis, and money management. Each course requires its own set of records. You’ll have to score high on all three in order to graduate.

Your first essential record is a spreadsheet of all your trades. You have to keep track of entries and exits, slippage and commissions, as well as profits and losses. Chapter 5, “Method—Technical Analysis” on trading channels will teach you to rate the quality of every trade, allowing you to compare performance across different markets and conditions. Another essential record shows the balance in your account at the end of each month. Plot it on a chart, creating an equity curve whose angle will tell you whether you are in gear with the market. The goal is a steady uptrend, punctuated by shallow declines. If your curve slopes down, it shows you’re not in tune with the markets and must reduce the size of your trades. A jagged equity curve tends to be a sign of impulsive trading.

Your trading diary is the third essential record. Whenever you enter a trade, print out the charts that prompted you to buy or sell. Paste them on the left page of a large notebook and write a few words explaining why you bought or sold, stating your profit objective and a stop. When you close out that trade, print out the charts again, paste them on the right page and write what you’ve learned from the completed trade.

These records are essential for all traders, and we will return to them later in Chapter 8, “The Organized Trader.” A shoebox crammed with confirmation slips does not qualify as a record-keeping system. Too many records? Not enough time? Want to skip high school and dive into neurosurgery? Traders fail because of impatience and lack of discipline. Good records set you apart from the market crowd and put you on the road to success.

Training for Battle

How much training you need depends on the job you want. If you want to be a janitor, an hour of training might do. Just learn to attach a mop to the right end of the broomstick and find a pail without holes. If, on the other hand, you want to fly an airplane or do surgery, you’ll have to learn a great deal more. Trading is closer to flying a plane than to mopping a floor, meaning you’ll need to invest a lot of time and energy in mastering this craft. Society mandates extensive training for pilots and doctors because their errors are so deadly. As a trader, you are free to be financially deadly to yourself—society does not care, because your loss is someone else’s gain. Flying and medicine have standards and yardsticks, as well as professional bodies to enforce them. In trading, you have to set up your own rules and be your own enforcer.

|

| Training For Battle |

1. The Gradual Assumption of Responsibility A flying school doesn’t put a beginner into a pilot’s seat on his first day. A medical student is lucky if he is allowed to take a patient’s temperature on his first day in the hospital. His superiors double-check him before he can advance to the next, slightly higher level of responsibility. How does this compare to the education of a new trader? There is nothing gradual about it. Most people start out on an impulse, after hearing a hot tip or a rumor of someone making money. A beginner has some cash burning a hole in his pocket. He gets a broker’s name out of a newspaper, FedExes him a check, and enters his first trade. Now he is starting to learn!When do they close this market? What is a gap opening? How come the market is up and my stock is down?

A “sink or swim” approach does not work in complex enterprises, such as flying or trading. It is exciting to jump in, but excitement is not what good traders are after. If you do not have a specific trading plan, you’re better off taking your money to Vegas. The outcome will be the same, but at least there they’ll throw in some free drinks.

If you are serious about learning to trade, start with a relatively small account and set a goal of learning to rade rather than making a lot of money in a hurry. Keep a trading diary and put a performance grade on every trade.

2. Constant Evaluations and Ratings The progress of a flying cadet or a medical student is measured by hundreds of tests. Teachers constantly rate knowledge, skills, and decision-making ability. A student with good results is given more responsibility, but if his performance slips, he has to study more and take more tests. Do traders go through a similar process? As long as you have money in your account, you can make impulsive trades, trying to weasel your way out of a hole. You can throw confirmation slips into a shoebox, and give them to your accountant at tax time. No one can force you to look at your test results, unless you do it yourself.

The market tests us all the time, but only a few pay attention. It gives a performance grade to every trade and posts those ratings, but few people know where to look them up. Another highly objective test is our equity curve. If you trade several markets, you can take this test in every one of them, as well as in your account as a whole. Do most of us take this test? No. Pilots and doctors must answer to their licensing bodies, but traders sneak out of class because no one takes attendance and their internal discipline is weak. Meanwhile, tests are a key part of trading discipline, essential for your victory in the markets. Keeping and reviewing records, as outlined later in this book, puts you a mile ahead of undisciplined competitors.

3. Training until Actions Become Automatic During one of my finals in medical school I was sent to examine a patient in a half-empty room. Suddenly I heard a noise from behind the curtain. I looked, and there was another patient—dying. “No pulse,” I yelled to another student, and together we put the man on the floor. I began pumping his chest, while the other fellow gave him mouth to mouth, one forced breath for four chest pumps. Neither of us could run for help, but someone opened the door and saw us. A reanimation team raced in, zapped the man with a defibrillator and pulled him out.

I never had to revive anyone before, but it worked the first time because I had five years of training. When the time came to act, I didn’t have to think. The point of training is to make actions automatic, allowing us to concentrate on strategy. What will you do if your stock jumps five points in your favor? Five points against you? What if your future goes limit up? Limit down? If you have to stop and think while you’re in a trade, you’re dead. You need to spend time preparing trading plans and deciding in advance what you will do when the market does any imaginable thing. Play those scenarios in your head, use your computer, and get yourself to the point where you do not have to ruminate about what to do if the market jumps.

The mature trader arrives at a stage where most trading actions have become nearly automatic. This gives you the freedom to think about strategy. You think about what you want to achieve, and less about tactics of how to achieve it. To reach that point, you need to trade for a long time. The longer you trade and the more trades you put on, the more you’ll learn. Trade a small size while learning and put on many trades. Remember, the first item on the agenda for a beginner is to learn how to trade, not to make money. Once you’ve learned to trade, money will follow.

Labels:

Trading Room

|

0

comments

Thursday, December 27, 2012

A REMEDY FOR SELF-DESTRUCTIVENESS

|

| Bad Luck |

People who like to complain about their bad luck are often experts in looking for trouble and snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. A friend in the construction business used to have a driver who dreamed of buying his own truck and working for himself. He saved money for years and finally paid cash for a huge brand-new truck. He quit his job, got gloriously drunk, and at the end of the day rolled his uninsured truck down an embankment—it was totaled, and the driver came back asking for his old job. Tragedy? Drama? Or fear of freedom and an unconscious wish for a safe job with a steady paycheck? Why do intelligent people with a track record of success keep losing money on one harebrained trade after another, stumbling from calamity to catastrophe? Ignorance? Bad luck? Or a hidden desire to fail? Many people have a self-destructive streak. My experience as a psychiatrist has convinced me that most people who complain about severe problems are in fact sabotaging themselves. I cannot change a patient’s external reality, but whenever I cure one of self-sabotage, he quickly resolves his external problems.

Self-destructiveness is such a pervasive human trait because civilization is built on controlling aggression. As we grow up, we are trained to control aggression against others—behave, do not push, be nice. Our aggression has to go somewhere, and many turn it against themselves, the only unprotected target. We turn our anger inward and learn to sabotage ourselves. Little wonder so many of us grow up fearful, inhibited, and shy.

Society has several defenses against the extremes of self-sabotage. The police will talk a potential suicide down from the roof, and the medical board will take the scalpel away from an accident-prone surgeon, but no one will stop a self-defeating trader. He can run amok in the financial markets, inflicting wounds on himself, while brokers and other traders gladly take his money. Financial markets lack protective controls against self-sabotage. Are you sabotaging yourself? The only way to find out is to keep good records, especially a Trader’s Journal and an equity curve, shown later in this book. The angle of your equity curve is an objective indicator of your behavior. If it slopes up, with few downticks, you’re doing well. If it points down, it shows you’re not in gear with the markets and possibly in a self-sabotage mode. When you observe that, reduce the size of your trades and spend more time with your Trader’s Journal figuring out what you’re doing.

You need to become a self-aware trader. Keep good records, learn from past mistakes, and do better in the future. Traders who lose money tend to feel ashamed. A bad loss feels like a nasty comment—most people just want to cover up, walk away, and never be seen again. Hiding doesn’t solve anything. Use the pain of a loss to turn yourself into a disciplined winner.

Losers Anonymous